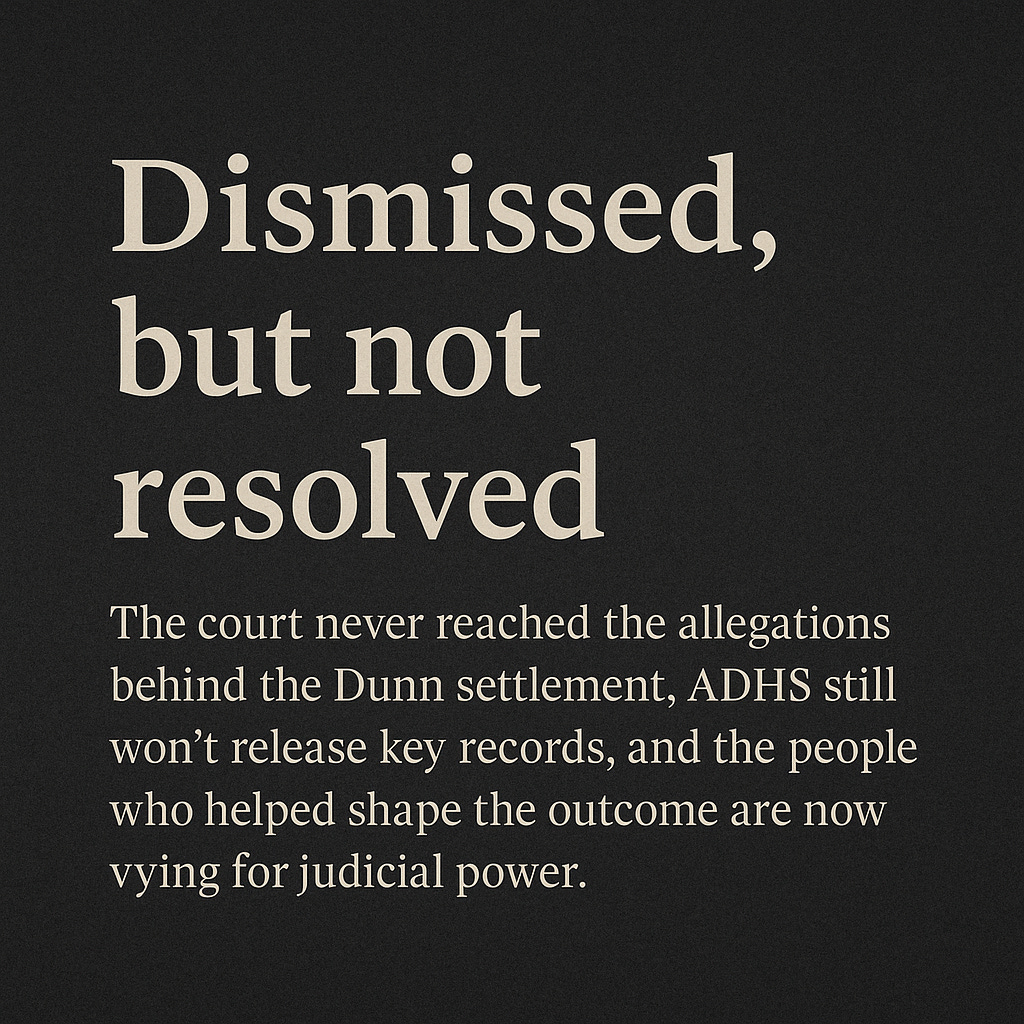

Dismissed, but not resolved

The court never reached the allegations behind the Dunn settlement, ADHS still won’t release key records, and the people who helped shape the outcome are now vying for judicial power.

Arizona’s long-running fight over a cannabis license that courts repeatedly deemed ineligible may have ended in a legal sense, but the dismissal has only widened the questions surrounding how that license was ultimately granted, how much the state has spent to defend it, and why several of the key players involved in the decision are now seeking judicial power.

Last month, Superior Court Judge Joseph Kreamer dismissed the case brought by Mason Cave and Arizona Wellness Center Springerville, finding that Cave lacked standing to challenge the Arizona Department of Health Services’ February 2024 settlement with Sherri Dunn, LLC, an entity controlled by Trulieve. Kreamer didn’t rule on whether ADHS broke state law or violated court orders. Instead, he sidestepped the underlying conflict altogether, holding that Cave did not have the right to bring the challenge. With that, the state’s position remains untested — and unexamined — in any court of record.

But outside the courtroom, the record paints a very different picture, one that suggests the real story of the Dunn settlement is not about standing or statutory interpretation but about access, political influence, opaque legal spending, and a regulatory system increasingly insulated from public scrutiny.

Public records obtained by Fourth Estate 48 show that since the settlement was finalized, ADHS has relied heavily on private law firms to manage everything from litigation to public records requests related to the controversy. Taft Law — now the lead firm handling ADHS’s public records productions and cannabis-related administrative litigation — has received millions in taxpayer dollars for its work on the Dunn matter and related disputes. Yet the department has provided no comprehensive accounting of how much Taft has been paid, how close the firm is to reaching its contract ceiling, or whether the contract cap has already been exceeded. When pressed for clarification, neither ADHS nor Taft responded.

Equally unclear is the timeline of Taft’s work. The firm’s invoices show substantial activity from December 2024 through mid-2025, but ADHS has produced no Taft billing records at all for the eleven months preceding the February 2024 settlement — the period when the agency was actively litigating the Dunn case, engaging with the Governor’s Office, and negotiating the final terms of the agreement. Records request logs and internal communications confirm that ADHS and its outside counsel were heavily engaged during those months, making the lack of documentation difficult to reconcile with the agency’s public position. Whether no work was performed, whether invoices were billed under different matter numbers, or whether key billing records were withheld remains unanswered.

Power, Pot, and Pay-to-Play

In early 2024, Arizona’s Department of Health Services (ADHS) quietly reversed itself and granted a highly valuable marijuana license to Sherri Dunn, LLC, a company managed by the CEO of cannabis giant Trulieve. The decision came d…

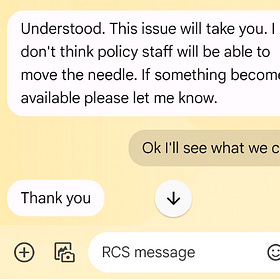

The ambiguity also sits uncomfortably alongside the documented political influence surrounding the settlement timeline. Texts released in earlier records show that in fall 2023 — after Sherri Dunn LLC lost in administrative and superior court — Trulieve lobbyist Wendy Briggs repeatedly contacted Gov. Katie Hobbs’ chief of staff, Chad Campbell, urging him to intervene. Briggs argued the matter presented financial exposure for ADHS and claimed the issue would “take you,” rather than policy staff. In October 2023, just weeks before the settlement discussions appear to have accelerated, cannabis interests including Briggs, the Arizona Dispensaries Association, and Trulieve contributed thousands of dollars to Hobbs and the Arizona Democratic Party.

Then, two weeks before the settlement was finalized, Briggs texted Campbell again: “Just wanted to thank you on Trulieve issue,” an expression of gratitude the Governor’s Office has never fully explained. The settlement was executed on February 14, 2024. Sherri Dunn LLC received its license within days. Cave, who raised the same arguments as Dunn, was never offered a settlement.

Throughout this period, ADHS’s legal and records-production strategy relied not only on Taft but on two firms whose contracts expanded significantly under Hobbs. Sherman & Howard’s contract ballooned from roughly $2 million to $7 million, a dramatic expansion that occurred as the firm took on more cannabis-related litigation and public records work for ADHS. (The firm merged with Taft in January.) Meanwhile, Coppersmith Brockelman — where attorney Andrew Gaona is a partner — secured multiple no-bid contracts to represent ADHS in sensitive matters, including disputes involving cannabis licensing, public records, and the Governor’s Office.

Gaona’s influence in Arizona’s cannabis and regulatory landscape is well-documented. He served as one of the architects of Proposition 207, the 2020 ballot measure that legalized recreational marijuana and created the dual-use licensing system at the heart of the Dunn dispute. He represents the Arizona Dispensaries Association (of which Trulieve is a member), and he has repeatedly represented the Governor’s Office in politically significant cases. His firm’s contracts give him visibility into regulatory disputes and administrative decisions that most lawyers never see. Plus, he is the brother of Hobbs’ deputy chief of staff Will Gaona.

Now, Gaona is seeking a new role: a seat on the Arizona Court of Appeals.

He is one of 17 applicants for the opening — 11 Democrats, 6 independents1, and no Republicans. Several applicants come from backgrounds that are noteworthy in their own right but Gaona stands out precisely because of his proximity to the cannabis industry, his representation of the Governor’s Office during the period in which the Dunn dispute unfolded, and his firm’s no-bid contracts with the same agency whose decisions are now shielded behind months of withheld records and escalating legal costs.

His application also comes just months after a major shift inside the Governor’s Office. Bo Dul, Hobbs’ former general counsel, left the administration to join Coppersmith Brockelman, where she now works directly alongside Gaona. The move reinforces how closely intertwined the Governor’s Office, ADHS, and their outside legal teams have become, even as ADHS continues resisting disclosure of documents tied to the Dunn settlement.

This convergence of political influence, legal contracting, and now judicial ambition raises questions that extend well beyond one cannabis license. When regulatory agencies route key decisions — and the public records that describe them — through private law firms operating under multimillion-dollar no-bid contracts, the practical effect is a system where transparency depends on private attorneys who have no incentive to err on the side of public disclosure. When the same attorneys or their firms then seek judgeships on the state’s appellate courts, the line between regulated industry, political power, and judicial authority becomes even more blurred.

Judge Kreamer’s dismissal leaves those structural questions unaddressed. His ruling did not answer why ADHS reversed course after years of consistent legal defeats, why it granted a multimillion-dollar license through a confidential settlement, why the Governor’s Office was aware of and engaged in discussions between Briggs and Campbell, or why the state has spent millions of public dollars fighting records requests related to the settlement. Nor did it answer why Cave — whose application was processed under the same statutory framework as Dunn’s — was never offered a settlement, despite raising identical arguments.

The case may be closed, but the public impact is not. ADHS continues to spend taxpayer dollars defending its decision and withholding records associated with it. The financial cost remains unknown. The contractual obligations remain unclear. And the key players involved are now moving into new positions of authority, including within the judiciary.

Arizona’s cannabis laws were written to create consistency, fairness, and predictable rules for applicants. Instead, the Dunn settlement has exposed a system where access, political connections, and private contracting appear to carry more weight than statutory deadlines or court rulings. Until the full record is released — including invoices, communications, and the internal analysis that led ADHS to reverse course — the public cannot know how one of the state’s most valuable licenses was truly decided.

The case’s dismissal does not mean the conduct Cave alleged didn’t occur; it means the court never reached that issue. Judge Kreamer ruled only on standing, not on whether anyone in the Governor’s Office exerted pressure behind the scenes. Campbell’s role — what he knew, what he communicated, and whether any influence was applied — remains unanswered. The only investigative record comes from the documents obtained so far, not from judicial fact-finding.

What is clear is this: a license twice ruled ineligible was awarded anyway, millions have been spent defending that decision behind closed doors, and several of the people who helped shape that outcome are now seeking judicial power. The dismissal may close the lawsuit, but it does not close the book on the policy, financial, and political consequences still unfolding around it.

Among the six applicants registered as independents, several have shifted party affiliation in recent years. Molly P. Brizgys became an independent after changing her registration earlier this year. Shalanda M. Looney has moved between parties, switching from Democrat to Republican in October 2023 over concerns related to the conflict in Gaza before returning to the Democratic Party in July 2024 to support Vice President Harris’s presidential run as a “Qualified Black Female Candidate.” Barry G. Stratford has the longest documented history of shifts: he was a registered Republican from 2003 through mid-2016, changed to an independent through 2020, briefly registered as a Democrat in February 2020 to participate in the Presidential Preference Election, and then returned to independent status in August 2020, where he remains. Grace M. Guisewite, Karen L. Johnson Stillwell, and Timothy W. Overton are the remaining independent applicants.